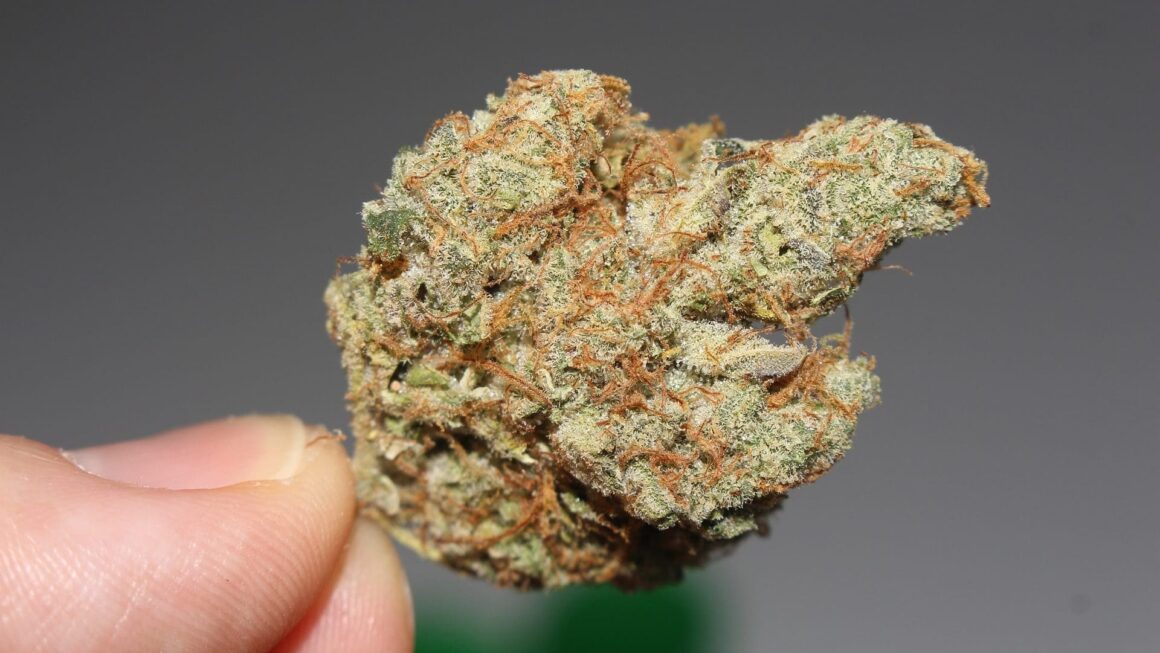

I’m in a bus on the Thika Super Highway, headed to Juja. It’s dark outside, but I leave my window open, loving how the wind feels against my face. My brother and I had a quick sesh before I left for home, and the THC is just now kicking in.

Gengetone music is blasting from the speakers, and as I nod my head along to the bassline, something my brother once said to me comes to mind.

“Why do artists feel the need to mention the fact that they smoke weed in every single song they write? Like, do they run out of subject matter, or what?”

I’m a musician who makes rap music, and I have mentioned weed in my songs from time to time, so I get a little defensive. I argue that it’s all about normalizing the use of cannabis.

When we spread awareness, we help people understand what cannabis is and what it isn’t, which goes a long way in reducing the stigma associated with it.

“Because otherwise, people look at us like we’re smokin’ crack!” I proclaim, passionately.

He’s not convinced.

“I can live with that. My problem is that young, influential artists are making catchy songs about ‘how great weed is’ and ten-year-old kids are dancing and singing along to them.”

I concede, saying that I see how that can be an issue, pass the joint back to him, and change the subject.

But as I sit in this matatu, vibing to the music, his point is proven. Pretty much every song alludes to smoking weed or mentions it outright.

I look around me. A group of young campus kids, drunk as sailors, are having a great time, singing along to every lyric.

But besides them, and myself, everyone else is a middle-aged person clearly on their way home from work. For the most part, everyone’s either on their phone or looking out the window.

Unperturbed.

Just a few years ago, the mere mention of cannabis would have had heads turning. Today, weed is so deeply embedded in Kenyan culture that it’s become impossible to escape it.

More importantly, even those who do not understand it have slowly come to accept it.

“And that’s why,” I should have argued, “everyone’s making songs and films about weed. The culture inspired the art, and not the other way around.”

While he may feel otherwise, I believe it’s a feat to be celebrated that we’ve single-handedly reframed cannabis from a taboo ‘narcotic’ to a cultural symbol of resistance, wellness, pleasure, and creativity. Here’s some context to give you an idea of how much ground we’ve covered.

Colonial Hangover: The Legal Backdrop

Before the British arrived in Kenya to gift us various goodies, among them displacement, segregation, and canvas safari boots, we all smoked weed. Different communities had different names for the herb, and communal festivals where people got high on ‘bangi’ and local booze, played music, danced, and played-fought were commonplace.

In 1914, several years into their rule, the British colonial administration introduced the Opium Ordinance, outlawing cannabis and starting the long history of cannabis prohibition.

When we regained our independence in 1963, we inherited these laws, and like a chronic hereditary illness, we’ve been unable to shake them to date.

Instead, in 1994, the Parliament passed the Narcotic Drugs & Psychotropic Substances (Control) Act into law, further cementing the prohibition of cannabis. This Act stated that it was against the law to cultivate, traffic, or possess cannabis, and outlined the consequences.

However, this Act allowed for the medical and industrial use of cannabis if regulations were enacted. They never were.

Between 2000 and 2010, law enforcement officials made a series of seizures. They also disrupted cannabis farming operations in Mt. Kenya, Western Kenya, and Lake Victoria. However, cannabis remained widely used.

Between 2017 and 2019, the late Kibra MP, Ken Okoth, who was being treated for cancer, introduced the Marijuana Control Bill. His goal? The decriminalization and regulation of cannabis. This heightened discourse surrounding medical and industrial use of cannabis.

In 2022, Presidential aspirant George Wajackoyah waved the ‘Legalize It’ flag, championing the medical benefits and economic implications. At this point, the conversation went national.

In 2023, a High Court ruling found that the Government of Kenya had neglected its duties by failing to implement licensing regulations for medical and industrial cannabis use as provided for under the 1994 Act. The Court ordered that the government must be compliant within 24 months.

But while lawmakers stall, the culture continues to take root, and young artists are at the forefront of shifting the perception.

Gengetone & Arbantone: Soundtracks of Normalization

When Gengetone became a mainstream sensation, I was in my last year of high school. Our principal, God bless her heart, didn’t want us listening to any of it.

The lyrics were raunchy, raw, and rebellious, leaving nothing to the imagination. Neither did the videos, which for the most part depicted house parties, vivid cannabis imagery, and lots and lots of twerking.

I didn’t care much for the music at the time, finding it a little under-produced, especially at its onset. However, something was exciting about how risque it was, and youth all over the country gobbled it up, hook, line, and sinker.

Groups like Ethic, Ochungulo Family, and Boondocks Gang waxed poetic about marijuana in pretty much all their songs. Just Imagine Africa humorously suggested that “kama hupendi bangi we ni mtoto was shetani,” which translates to “if you don’t love weed you must be a child of the devil”.

Lil Maina’s first big single was a bop called Kishash, named after one of the many street names we have for cannabis. It’s a song about enjoying good weed at a bash with good friends. He raps:

“Depression ikikick in manze nitakiburn,” loosely translating to “When I feel depressed, a little weed goes a long way.”

This was one of the biggest tracks between 2022 and 2023, garnering close to 10 million streams on YouTube alone. Lil Maina may not write about cannabis so overtly anymore, but he drops slick references now and then.

When the hype around Gengetone died down, Arbantone was already crossing the threshold. This innovative genre samples local and international dancehall classics, adding a modern twist.

While this music is incredibly fun to party to, it does much more than set the soundtrack for a good time.

Just a year ago, we had an Arbantone protest anthem when we took to the streets to demonstrate against corruption, high taxation, and police brutality. Hundreds of thousands took to the streets with whistles, footballs, and Bluetooth speakers, and we danced to Anguka Nayo.

This anthem has become a part of pop culture, and everyone 50 years and younger knows it.

Cannabis in Hip-Hop

It’s almost expected for young people to make songs about weed, but it’s a whole other thing when older, more established hip-hop artists do it. Personally, I think it helps with the cause.

When Wakadinali released their album in 2023, I was immediately drawn to Mariwana. They sampled a Wajackoyah soundbite on the album, so I was prepared for what was to come.

The song itself is a beautiful love letter to cannabis, with the guys writing thoughtful verses about what cannabis means to them. They also detail their first encounter with the herb, making for a relatable and enjoyable listen.

It’s no surprise that that’s one of their fan favourites from that project. The innovative video for the song, featuring puppets, has garnered nearly 5 million views on YouTube.

Kenyan Hip-Hop icon Octopizzo did the same thing, releasing at least two cannabis-inspired joints in one album. One was King Size.

In One More Time, a reggae-rap vibe that’s perfect for a morning sesh, he instructs, “Asha ngwai, asha ngwai,” meaning “Light that weed.”

And years before that, he released Wakiritho with the Gengetone group Sailors. To me, he was passing the torch, or the joint, if you will, to the new generation. More importantly, however, was the message this sent to his own generation.

The reality is that cannabis in music normalizes use in everyday speech. It educates the world that people who enjoy weed exist, reduces the stigma, and ideally even makes non-smokers more tolerant.

Bensoul: Kenya’s Cannabis Brand Ambassador

Few Kenyan artists are as dedicated to the legalization cause as Bensoul. While many choose to keep their love for cannabis on the low, afraid it will tarnish their image and cost them millions in brand deals, Bensoul is not one to shy away.

On 4/20 in 2020, when we were all cooped up in our homes, he released an EP. On it was Peddi, a song named after the slang term for cannabis peddlers, or plugs.

This is a love song, though, and on it, he croons: If you’ve been looking for a love peddler, then I hope you’re ready.

It’s a cheeky play on a popular slang term that everyone relates to, which made the song an instant hit.

In the video, he’s at a serene location smoking. It’s the first time a mainstream artist smoked so brazenly on camera. This was the beginning of a long-standing tradition: dropping cannabis-themed music every year on 4/20.

The following year, he released Sweet Sensi, a beautifully-produced love letter to marijuana. On this Reggae smash, Bensoul sings of his love for cannabis like a poet yearning for his lover.

“And when I think about the special place I keep my lighter

I can’t wait to get home, and light it up

You don’t know how, you don’t know how, you don’t know how good that feels

And when I think about the special place I keep my sensi

I can’t wait to get home, and light it up

You don’t know how, you don’t know how, you don’t know how good that feels.”

Everything about this song works, from the drums to the bassline to the enchanting horns that transport you right to the beach. It makes you feel like reaching for another joint, and you should, ‘cause that’s what Bensoul would do.

His debut album, released in 2023, took on the politics of decriminalization in even more depth. In Legalization featuring Lavosti, Bensoul hopes that he will see a time when we’ll be able to indulge freely in cannabis. When young, enterprising Kenyans can participate in the cannabis industry without discrimination or criminalization. He urges us not to lose hope and to keep fighting the good fight.

“I dream of a day/ When I will find on the menu/ A strain of a Kenyan grade/ On Moi Avenue,” he sings.

Watching him perform these songs live, it’s hard not to be moved to tears. The audience knows every word, and they resonate deeply. Lighter flicks ring out so often it’s got to be a fire hazard. By the end of the night, the entire venue reeks of weed, and we walk away healed, satiated, and glass-eyed.

When cannabis becomes legal in Kenya, Bensoul will be the first person to celebrate. And we’ll be there, revelling in the music as we live the prophecy of his pen.

Fashion & Visual Art: A Growing Green Aesthetic

Walking around town, you see more cannabis branding now than ever before. Rather than keeping their love for weed a secret, people wear it boldly. Whether it’s on a bandana, bucket hat, graphic tee, or printed all over a pair of socks, the cannabis leaf is more ubiquitous than it’s ever been.

Chains with cannabis leaf pendants are also common, and while I don’t own, and likely wouldn’t wear one, I must admit they do look pretty cool. So do the beaded Rastafarian flag bracelets that always seem to catch my eye when I’m out and about.

Even graffiti artists incorporate the cannabis leaf in their murals or depict cannabis use in some other way in their art. It’s almost as though everyone’s working together to spread the good Green Gospel, but the best part is it’s all happening organically.

Global Influences in the Local Context

Kenyans consume lots of American Hip-Hop and Jamaican roots-reggae music. In fact, one of my earliest memories is my mom bathing me while Fat Joe’s “Make It Rain” blasted from the neighbour’s boombox.

Step into a barbershop, khat den or matatu anywhere in the country, and chances are they’re playing Don Carlos, Israel Vibration, or Culture.

These two cultures have played a huge role in normalizing cannabis globally, including here in Kenya. We grew up watching rappers smoke Backwoods and our older cousins get caught in a trance listening to Bob Marley.

However, in rural areas where folks have no idea who Snoop Dogg and Wiz Khalifa are, local music has been the biggest influencer for cannabis normalization.

Today, cannabis culture is no longer imported; it’s rooted in Kenyan slang, music, and style, thriving in various youth subcultures across the country.

In Canada and the United States, the decriminalization, legalization, and normalization of cannabis came after its cultural normalization. Kenya is at a crucial tipping point, where culture leads while the law follows behind.

I’m confident it will catch up soon.

But for now…

The Stigma Erodes, & Perceptions Are Changing

When my mother found out I smoked weed a few years ago, she was mortified. She was scared for me, afraid that I’d spiral into psychosis, become unemployable, and become a thief to support my drug habit.

To her, my smoking weed wasn’t an informed choice; it was a moral failing.

I understood where she was coming from, but I made it clear that it would be almost impossible to have an objective conversation until she shifted her perspective.

Over the years, I’ve seen a huge change. Today, she coyly refers to it as ‘that pastime of yours’. Not habit. Pastime. That’s growth if you ask me.

In my opinion, the youth normalizing recreational cannabis use and being willing to have open conversations about it with their parents has significantly helped erode the stigma.

When we have nothing to hide, it proves that we have nothing to be ashamed of.

In Kenya, cannabis culture continues to thrive because we refuse to let outdated colonial laws stifle our creativity. Policy is bound to catch up eventually; in the meantime, we’ll continue using our music, fashion, and visual art to reshape how Kenyans see cannabis.

This article is from an external, unpaid contributor. It does not represent High Times’ reporting and has not been edited for content or accuracy.