Stephen Baldwin logs onto Zoom like a neighbor who has a good story ready. He is warm, quick with a joke, and happy to drift between family memories, faith, and flowers. Within a minute, he is recalling smoke-filled rooms from his Long Island childhood and a Jim Morrison soundtrack that still rings in his ears.

He is also tying it to his own family tree. The Doors’ keyboardist Ray Manzarek once cited Brazilian jazz great Eumir Deodato as an influence. Deodato is Baldwin’s father-in-law. In other words, Baldwin’s personal history has always had a little High Times energy humming in the background.

By now, Baldwin’s a familiar face from the golden age of Gen-X and Millennial cinema: The Usual Suspects, Bio-Dome, Half Baked, Threesome, The Flintstones in Viva Rock Vegas. He’s played cult icons, comic relief, and more than a few wildcards—the kind of actor who seems equally at home in chaos or comedy. That same blend of mischief and discipline carries straight into how he talks about cannabis, faith, and family today.

Over the next hour, we covered it all: his first encounters with cannabis, what “Cali Sober” means to him at 59, and how New York’s green rush collides with old ideas about sobriety. The conversation also wound through the Baldwin Fund—the nonprofit his late mother founded to fuel breast-cancer research—and his newest creative kick, a hilariously honest podcast called One Bad Movie. And, naturally, there’s a classic Baldwin family story in the mix, complete with Rosie O’Donnell and a dose of stubborn love.

From Smoke-Filled Rooms to Cali Sober

Everyone has a High Times origin story. Baldwin starts as the youngest of four brothers in a house that never sat still.

“I’m the youngest of the Baldwin brothers. When I was in seventh grade, Billy was in ninth, Daniel was in tenth or eleventh, and Alec was a senior. I just remember seven, eight, and nine-year-olds being in smoke-filled rooms listening to Jim Morrison and The Doors,” he laughs. “That beginning of ‘Riders on the Storm’, that whole slow keyboard thing. That is my stoner High Times six degrees of Kevin Bacon.”

Adulthood brought a hard pivot. Baldwin chose sobriety in his mid-thirties and stayed the course for more than twenty years. He speaks about that season with respect and zero judgment for anyone who still needs a no-substance path. What changed in his late fifties was his body and his priorities.

“I was sober, completely sober. Every January twenty-first is my sobriety birthday, until about four years ago,” he says. “For me, it was simple. There are older guys out there dealing with inflammation and sports injuries and all kinds of stuff. CBD is great, but medical cannabis, the medical science of medical-grade cannabis, is the future. It is undeniable.”

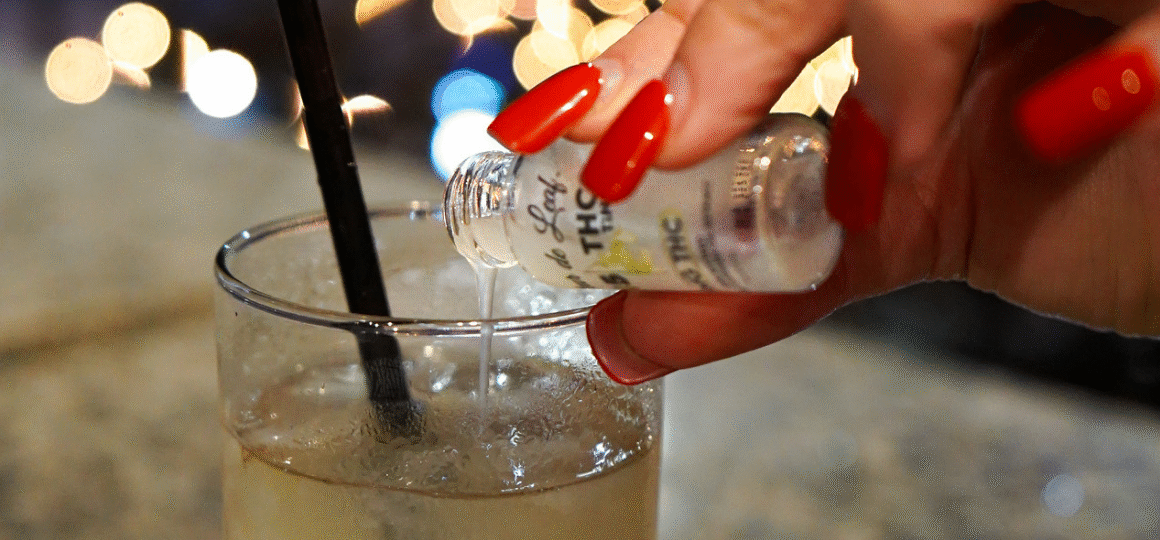

He started conservatively with oil and tinctures. Today, his routine is simple and not performative.

“I am a daily partaker in flower,” he says. “I do not enjoy stuff that is infused with all this other this and that. I am old school. A couple of gummies here and there if I feel like it. Maybe every third day. And even then, it is only up to like twenty-five milligrams.” The non-negotiable rule is no couch lock. “I do not have time for that.”

He uses the term Cali Sober and does so without a wink.

“I needed to kind of come out of the closet, the cannabis closet,” he jokes. “I said it on Jamie Kennedy’s show. I am Cali Sober, and yeah, I use cannabis. And if you do not know the benefits, then you are just crazy. Do the research and know the difference between using it beneficially and using it in a non-beneficial way.”

Baldwin is direct about the social friction that can come with any change in a sober identity. He has lost a few friends over it and still fields morning calls from his big brother, who does not use cannabis.

“Alec calls me every morning after I have partaken of my vitamins,” he says, laughing. “He will interview me. How do you feel? I feel great. I have not even had coffee, and I can deal with you.”

The case he makes is not mystical. It is practical and biological.

“If you take Advil or ibuprofen, those are synthetic things that have to pass through your liver,” he says. “Now I can see research that says there are receptors in [our bodies] made for cannabinoids. There would be no receptor for cannabinoids inside the human body if it were not naturally meant to be so.”

When Cannabis and Cancer Research Cross Paths

Baldwin lives upstate and has watched the legal market expand in what feels like a lapse.

“It has been a short period of time,” he says. “The number of dispensaries going up in the state of New York, I do not know what the limit is going to be, but it is going to be thousands.”

He is clear-eyed about the national picture. It is still a patchwork. It still creates headaches for supply and for companies that operate in multiple states.

“It is still a bit of the wild wild west and it is still a bit of a gold rush,” he says. “Cannabis from one state is not supposed to cross over to other states. There is a long way to go.”

Celebrity brands do not impress him. Smart cultivation and well-run operations do.

“I toured a very large California facility. Fantastic,” he says. “Then I went and saw Curaleaf, which was mind-blowing. Curaleaf’s facility is stunning. There must be dozens of really smart investors lining up now. But the bricks and mortar still matter. Customers need to walk into the store.”

When medical cannabis arrived in New York, Baldwin did what a lot of smart patients do. He went where the staff would talk and teach. Curaleaf became his regular stop near home in Newburgh. A conversation with a budtender who had lost her mother to breast cancer started a chain of events. Weeks later, he met a New York operations lead who shared a similar personal story.

The timing lined up with Breast Cancer Awareness Month planning. The result is a straightforward October activation inside Curaleaf’s New York dispensaries. At checkout, customers can round their total to the nearest dollar and donate the spare change to the Baldwin Fund.

“This is our first connection and partnership from my family’s organization to any cannabis company,” he says. “It is almost beyond belief how this came together. What connects people is people.”

That is the extent of the pitch. No brand fireworks. No product laundry list. The point is the pathway. A dispensary becomes a place where spare change can move from a counter screen to a research budget.

“People think eighteen cents or seventy-five cents does not matter,” Baldwin says. “It really makes a difference.”

If you live in New York and stop into a Curaleaf dispensary this October, say yes when the screen asks to round up for the Baldwin Fund. That little bit of change turns into research money. If you want to go deeper, follow the Fund’s channels, read survivor stories, and keep an eye on community events.

The Fund operates with a simple engine. Small acts multiplied into grants. Grants are directed to researchers with promising ideas. Results are shared back so that families can see progress in real time.

The Baldwin Fund: Tenacity, Family, and Calling Rosie O’Donnell

Before the partnership, before the round-up screen at a register, Carol M. Baldwin was dialing a newsroom like a character in a sitcom who never learned the word no.

“After my mom launched what was previously the Carol Baldwin Breast Cancer Research Fund, now called the Baldwin Fund, when she got started, it was a super duper small town,” Baldwin says. “A lot of community building, small events.”

She wanted help from Rosie O’Donnell, who at the time had the most powerful show in daytime. Alec told his mother that that is not how television works. You do not just call Rosie.

“My mother literally picked up the phone and called NBC to get to Rosie O’Donnell,” Baldwin says, still delighted. “It was like a sitcom. Rosie is on a speakerphone, and somebody goes, Rosie, Alec Baldwin’s mother is on line four. Rosie picks up the phone, talks to my mother, and then books her on the show. That is the tenaciousness of the Baldwin family.”

The Fund grew up from that exact spirit. It kept the small-town feel and added real scale. There are black tie galas in Syracuse. There are busy weekends of golf tournaments. There are neighborhood events where people give what they can. There is a man who feeds the homeless and donates the proceeds to the Fund.

“The best part of humanity is the pay-it-forward community,” Baldwin says. “Every new year and every event and every expansion of the Baldwin Fund community in New York, the more you hear these incredible stories. Not just people who are battling. It is the unsung heroes.”

The results are measurable. “We have given over, I think it is over fifty or sixty, fifty thousand dollar research grants since the inception,” he says. “One of them has led to a very significant response to metastatic cancer and opened the door to more information and positive research to find a cure.”

His sister Elizabeth leads the Fund today. Baldwin helps where his voice and network add value. He is not interested in turning cancer work into branding. He is interested in research and outcomes.

On Creativity, Comedy, and One Bad Movie

I asked if cannabis sparks his creativity. His answer was pretty clear: No. Not exactly. He laughs at the idea that he needs any extra octane to get weird.

“I do not need cannabis for creativity. I am probably weirder and funnier on my own,” he says. “The greatest advantage is twofold. Some strains can focus in that ADD kind of way. That is beneficial. It helps me be more focused. I do not try to find cannabis that expands my mind. I just want to be me and be pain-free and be relaxed.”

Ask Baldwin about the thing that makes him light up right now, and he will talk about a podcast that lets actors roast their own careers with love. One Bad Movie is exactly what the title promises. Each episode invites a guest to revisit a project that was panned, pulpy, misunderstood, or just a paycheck. The stories are honest and funny. They also give audiences a look at the craft and chaos behind the credits.

“I am interviewing actors about their bad movies. It is extremely funny,” he says. “When I launched the idea, I was in the car listening to a guy do the same press interview answer over and over. I said ‘Would it not be cool to hear him talk about his one bad movie.’ One bad movie. I kept saying it. Then I called my partner, and he burst out laughing. Thus, the idea was born.”

Some conversations drift toward gossip and legend. Some turn into mini film school lessons. Some land the perfect punch line. Baldwin’s most-watched episode features Michael Madsen, recorded before Madsen passed away in 2024. Baldwin treasures a single exchange.

“I turned to him and said, So Mike, obviously your one bad movie is Free Willy,” he says. “He goes, Oh, no. I did not want to. They told me to do the movie. I went to the first meeting and said, What do I do, kill the whale?”

The show often holds up a mirror to Baldwin himself. When an editor asked how many of his own films fit the format, Baldwin guessed seven. The count came back much higher.

“Out of a hundred, I think twenty-seven of my films are bad movies, apparently, that I just did for the money,” he says, cracking up. “Look up Earthstorm. And another brilliant performance by Steve Baldwin is Sharks in Venice.”

How does he classify Half Baked? He smiles and lands it right in the sweet spot.

“Half Baked is kind of a bad movie. It is a great bad movie. It is the performances and the subject matter that make it interesting. I hope that is not cannabis heresy.”

Recent episodes of his podcast include Rumer Willis. Baldwin teased her about talking through any misfires from her famous parents. She was a good sport and then brought a sharp perspective of her own. He hints at a slate expansion in early 2026 as distribution lands. He is also circling a directing offer that should make genre fans happy.

“I just got offered to direct a film that is between a sci-fi and a slasher,” he says. “They are setting it in the seventies at a certain event. Imagine a period piece at a well-known event, then all of a sudden, murders start to occur. It is clever and it is going to be fun.”

The bigger point is that laughter itself feels like wellness.

“The best medicine for me now is laughter,” he says. “Sharing the love, the light, and laughter.”

Final Hits

A few asides reveal the person behind the public stories. Baldwin jokes that he answers to a boss of 39 years when his wife pulls into the driveway. He calls his morning cannabis his vitamins. He fields his brother’s daily check-ins with patience and humor. It’s a family that argues, ribs, forgives, and keeps showing up.

At 59, Baldwin isn’t selling reinvention—he’s living alignment. Cannabis helps him sleep, stay calm, and move without pain, not chase a high. That choice sits alongside a family mission that channels loose change into real cancer research, helping patients today, not someday.

The October round-up at Curaleaf’s New York dispensaries is just one small bridge between those worlds: a moment at the counter that becomes momentum in the lab. Around that work, Baldwin is building space for laughter with One Bad Movie and keeping his own practice simple.

Old-school flower. Clear head. Real causes.

A man who knows exactly what he wants his name attached to—and why.

Images courtesy of Mattio Communications.